Introduction to Ice in Every Carriage

Next to the historic reconciliation between France and Germany, few developments in the 1950s were more surprising – and perhaps in the long run more rewarding – than the invitation of Asian leaders, first of all from Indians, to an unofficial American, Frank Buchman, to come to their continent to spread the ideas of ‘moral re-armament’ as essential elements in the newly independent regimes that were springing up across the continent. After all, Asian spokesmen are very proud of their own spiritual traditions. Not many Western pundits have highlighted this unusual invitation and its consequences. Indeed, Moscow spotted the ideological significance more quickly than they did. Here for the first time is the inside story of this odyssey, told by those who took part in it. It reveals an utterly extraordinary impact on a subcontinent near the start of its independent career.

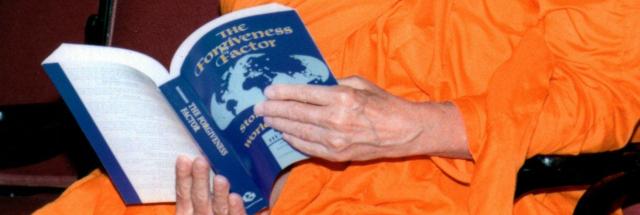

Photos from the top down:

Stage equipment at Nedous Hotel in Srinagar, Kashmir

A piano is delivered for performances in Hyderabad

Erecting a stage at the Metropole Hotel in Karachi

Sound engineer Jack Dickson, UK, and stage manager Jarvis Harriman, USA

Outdoor showing of Jotham Valley for 5000 people in Madras

The 'Jotham Valley' quartet sings to the driver and fireman on the special train

In 1952 Dave Walley, an American, 22, Bob Cook, a Canadian, 21, and I, an Englishman, 20, flew out to Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then called, to build scenery for four plays that were to go on a tour of Asian nations. We were part of the advance group led by Frank Buchman. It was only five years after Indian independence and seven years after the devastation of World War II.

In 1952 Dave Walley, an American, 22, Bob Cook, a Canadian, 21, and I, an Englishman, 20, flew out to Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then called, to build scenery for four plays that were to go on a tour of Asian nations. We were part of the advance group led by Frank Buchman. It was only five years after Indian independence and seven years after the devastation of World War II.

Dave, Bob and I lived and worked in the Young Men’s Buddhist Association hostel in Colombo. A large kettle of mixed tea and milk that brewed for hours on the stove, the incessant cawing of the crows outside in the street, and the huge blister that developed in the palm of my hand as I tried to drill screws into the teak wood for the stage ‘flats’ – these are vivid memories I retain of the first days. It was a dramatic introduction to Asia.

Today world travel, even for the young, is taken for granted. A ‘gap year’ backpacking in say Brazil or Thailand, or school sporting teams travelling the continents, is not thought out of the ordinary. But nearly sixty years ago this was not the case and certainly not the idea that you would take 200 people and four stage plays on an eight-month Asian tour.

Those of us who participated then have done other things in life and hardly ever have we thought back to those earlier years. Yet one begins to ask, and is asked by others, what it was all about. Did it really happen?

Those of us who participated then have done other things in life and hardly ever have we thought back to those earlier years. Yet one begins to ask, and is asked by others, what it was all about. Did it really happen?

Thinking about it, a few of us decided to revisit those experiences as much in awe of the logistical as much as of any socio-political significance. In undertaking this task we have been encouraged by dozens of others who were with us on the trip. Who participated and why, what actually was done and what effect did this historic journey have both on those who participated and those who were reached? What is the legacy of this venture?

The responses to these questions put flesh on the bones of this account. As Dave Walley emailed me, recounting his memories: ‘They were an adventure for me – akin to the atmosphere in the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. When I look back at it, there comes a definite flush of excitement, even now.’ And cast member Carol Deane wrote, ‘That nine months or whatever, I consider not only my coming of age but a very exciting time, if not the most.’

Joti van Os sums it up, ‘Joining the team and being able to share through our musicals, our lives with each other but also with all those people in the different countries who came to our musicals was a tremendous privilege. For me with the years I had just spent in a Japanese concentration camp and getting forced to emigrate from Indonesia to the Netherlands, devastating years when you are just twenty, being able to join a positive, life-giving force was “manna” for my soul and it saved my life. I was able to find real healing. I am 82 now and I fully realise that today all around the world people my age are sharing the fate I had to live with. Our plays and message then, a  message born in our heart and minds, is still so relevant today in the Middle East, Afghanistan, even in Europe. And just like we did after World War II, my hope is that also today we will and we shall find young people who will rise to the challenging times we live in in 2009.’

message born in our heart and minds, is still so relevant today in the Middle East, Afghanistan, even in Europe. And just like we did after World War II, my hope is that also today we will and we shall find young people who will rise to the challenging times we live in in 2009.’

The stage crew of which we were part comprised more than twenty young men and a few young women who looked after the sound, the lights, the carpentry, the costumes, the makeup and the props. The schedule of plays was very full with all sorts of extra performances fitted in, even three in a day, but even so we managed to participate in many of the other memorable activities. In nautical terms, it is a view as much from the engine room as the bridge. Or as one early reader of the manuscript put it: ‘we are obviously working on two levels: 1) statesmanship level, and 2) monkey level! The ideological and the nitty-gritty practical were worlds apart.’

Paul Trog, from Switzerland, feels that the energy generated by the team came from ‘a shared belief in God and reinforced by a unique group dynamic, rooted in bonds of friendship’. He writes that ‘a common, enthusiastic commitment to plant a moral ideology into the nascent Indian democracy lifted everyone beyond the realm of just what was possible’. As a carpenter as well as a cast member he finds that his memory of the backstage achievements still leaves him in awe and incredulous.

All of us survivors are in our seventies or eighties and have some difficulty remembering with any clarity what happened and in what order. Even contemporary accounts differ in details in their reporting of some events. But we have tried as far as is possible to be accurate and, I hope, to convey the ‘excitement’ of which Walley writes.

All of us survivors are in our seventies or eighties and have some difficulty remembering with any clarity what happened and in what order. Even contemporary accounts differ in details in their reporting of some events. But we have tried as far as is possible to be accurate and, I hope, to convey the ‘excitement’ of which Walley writes.

Like others, I have memories personal to me. Working backstage in Bombay (now Mumbai) with the president of the cement workers of India and having him say to me, as we swept the stage, ‘You know this is the first manual work I have ever done.’ Celebrating my 21st birthday with two performances of the plays in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Delivering press releases by autorickshaw to newspaper offices through the crowded streets of old Delhi. Assailed by prickly heat in Madras (now Chennai). Enduring the frightening road trip through the Banihal Pass into Kashmir. Accompanying Buchman to where he had played polo with the Maharaja in Gulmarg and having a first sight of K2. Playing golf with Farooq, son of Prime Minister Sheikh Abdullah, in Srinagar and taking tea with the Prince of Berar in Hyderabad. And, in the glorious lack of proportion of the young, being personally very annoyed that I had to give up playing in a field hockey match for the Roshanara Club because Prime Minister Nehru was coming to tea. I was there at the start, building the stage ‘flats’ in Colombo, and I was there at the end as I bade farewell to the Karachi camel cart carrying them away.

Seeing starving people outside our dining car as we stopped in a station, the conviction was confirmed in me that my life should be used for more than just my own advancement or satisfaction. And it was on this trip I had my first article published, in Calcutta’s Amrita Bazar Patrika.